Interview with Professor Steven Chu

Category: Interviews,Nobel Prize -

Tags: All Researchers,University Directors

Table of Content

- Introduction

- Professor Chu’s Tips for Students in a Nutshell:

- Teaching Scientific writing

- Writing grant proposals

- Exemplary writing style paper

- Scientifict writing styles

- Exemplary papers

- Communicating terms to nonscientists

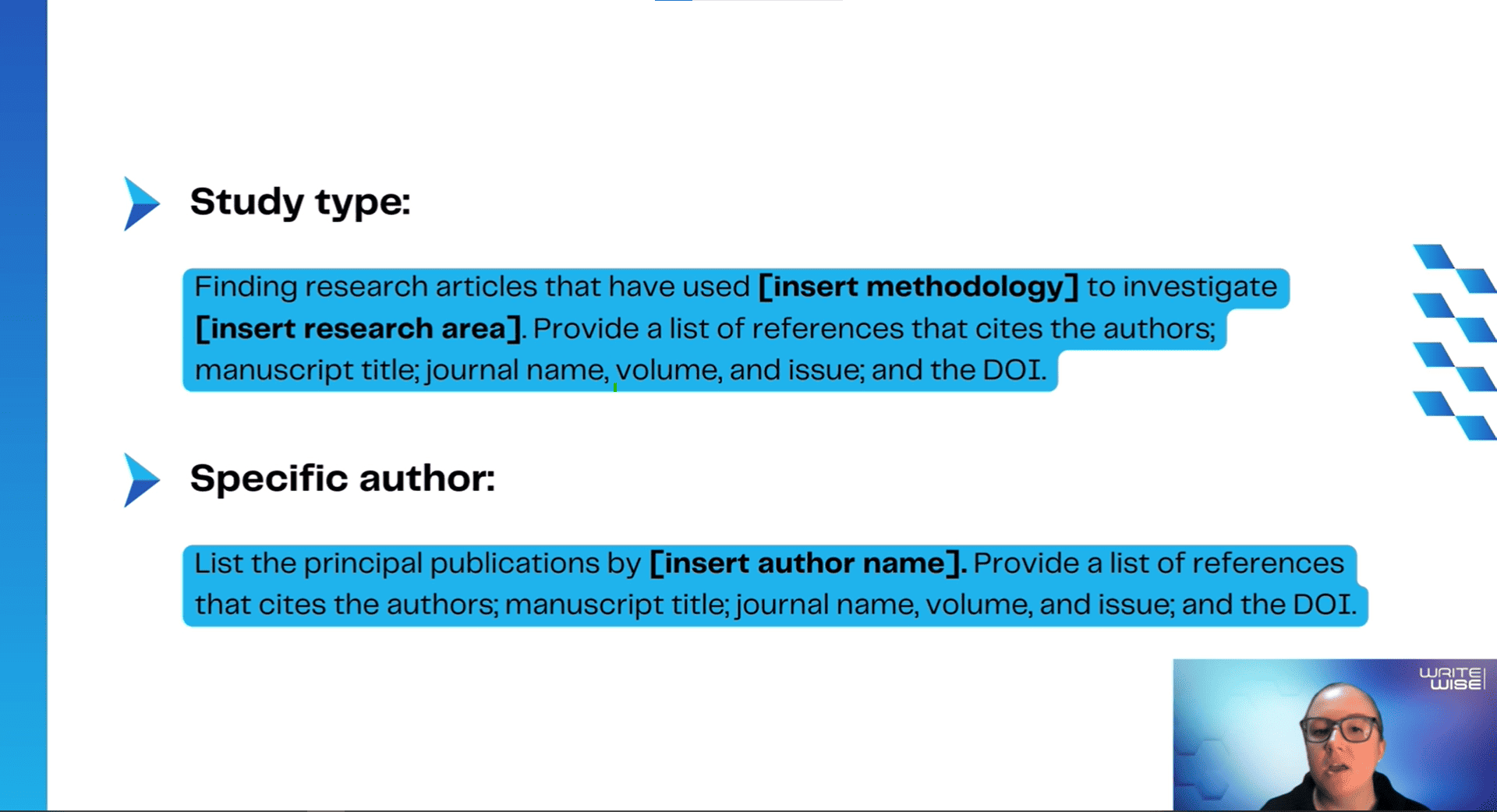

- Mastering Bibliography for project

- Top Udemy ChatGPT Course – Take Your Academic Writing to a New Level!

- AI Writer for Academic Writing in Markdown Format

- Top 10 Best Productivity Hacks That Work

- WriteWise: National and International Recognition

- Recognition by HolonIQ: Top 200 Women in Edtech + LATAM EdTech 100

- 5 Easy Steps to Master the Format of the Bibliography for Project

- Among vs. Amongst

- The Art of Implication meaning

- Do you want to learn how to use ChatGPT for Academic Writing?

Reading Time 8.3 minutes

Introduction

WriteWise had the honor and pleasure of interviewing Professor Steven Chu, 1997 Nobel Prize in Physics, former U.S. Secretary of Energy (2009-2013) and Professor of Physics and Molecular & Cellular Physiology in the Medical School at Stanford University.

Professor Chu has published over 260 papers in top-tier journal of his discipline, including PNAS, eLife, Nature, Physics Reviews Letters, among many others

Professor Chu’s Tips for Students in a Nutshell:

-

Writing logically usually means thinking logically. Try to present your manuscript in a linear method – A, B, C not C, A, B.

-

Writing grants is a lot like writing papers, but in a grant, it is important to clearly explain why your research will be new and different from what already exists.

-

Professor Chu provides interesting insight into the different standards for reproducing experiments between the fields of physics and biology.

-

To present to non-specialist audiences, you first need to determine their existing level of knowledge.

-

Reading body language is crucial to communicate with non-specialist or non-scientific audiences.

-

When presenting, talk with your audience! Engage them to determine if they understand what you are saying.

-

Professor Chu recommends the following papers as examples of good writing: Laser Cooling of Atoms, Ions or Molecules by Coherent Scattering, Vladan Vuletić and Steven Chu, Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 3787 (2000).

Teaching Scientific writing

[WriteWise]

You have published many papers in the most prestigious journals in the world. How do you transmit this experience to your students? What is your strategy to teach your students scientific writing?

[Professor Chu]

[In] most cases, you ask the students to write the first draft. [And] in most cases, the first draft is terrible. You know, one thought doesn’t follow another thought. So, at that point I look at it and do corrections….[I]f it’s not that bad, I just [make] corrections and pass it back to the student. I don’t put corrections and submit it, otherwise the student doesn’t [learn]. And half the time…I actually sit down with the student and say, “You said this, and this is why I [changed] it.” [I] tell them why I did it.

[This is] very important. I can spend a third of the time teaching [students] how to write…I’ve found over the years that teaching them how to write is teaching them how to think logically and not miss steps. [When writing a paper, you have] to anticipate the reader, who doesn’t know what you did… [You have to] explain things in a linear fashion, build it up as a process, A to B to C to D, not A to D to F to B.

Writing grant proposals

[WriteWise]

You have been awarded many grants. When writing your grant proposals, do you have a methodology or strategy to effectively structure the information you want to present? What tips do you have for students to effectively write a grant proposal, which is another type of scientific writing?

[Professor Chu]

It’s more or less the same, but in [the case of grants] you try to explain what has been done before, what you want to do, what’s really new, as simply as you can. The number of references is less [than in manuscripts], but you still have to put in the critical references…It’s also very clear writing. And you also have to explain what’s different. Is this new and why is it new? But you have to [present the project] in a way that doesn’t over exaggerate what’s going on.

Exemplary writing style paper

[WriteWise]

Is there any paper that you have published that you would consider exemplary in terms of writing style? Not in terms of scientific quality but in terms of scientific writing.

[Professor Codogno]

[Distinct classes of phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinases are involved in signaling pathways that control macroautophagy in HT-29 cells, Petiot A, et al., 275[2]: 992-8, 14 January 2000]

This paper is published in JBC, but is very highly cited because it came at the right moment at the right place regarding equations of macroautophagy. Of course I realized this at the moment, but 15 years on, I realize why this paper [is so cited]. Yes, I am satisfied with this paper.

This paper was very surprising…I remember when I received the feedback from the journal, I thought it was rejected because there were no comments. I just read from the editor, and there was one sentence in the letter that the paper was accepted with no modifications. Well, this was the first time and the last time that [a paper of mine] was accepted with no modifications!

Scientifict writing styles

[WriteWise]

You have published in many and diverse journals, from physics journals to biology journals. When you write papers for such different journals and such different audiences, do you have differences in your style of writing, or do you basically use exactly the same logic?

[Professor Chu]

The logic is the same, the audience is very different. You still have the fundamental things; you have to explain [everything] very clearly, think linearly…What I find difficult is to make the transition between biology, medicine, things like that and mathematics…I find that sometimes the reviewers think something is true because it’s been accepted, but half the things in biology I find out are not true. [Biology] is not as precise [as physics], and the experiments are hard to repeat….the standard is much lower in reproducibility [than in physics]….

In most [physics] laboratories, if it happens [only] twice, you won’t publish it. I was doing something that was only happening half the time, and it delayed publication…[This was with] the first optical tweezing of a DNA first single module, and, you know, we’d been talking about it for two years…and people [said], “Haven’t you published it yet?” and [we] said “No, because it only works half the time.” “Well, how many times have you tried it?” “Well, dozens.” “You’re kidding,” they said, “Your kidding, you’ve did dozens of times and it works half the time? That [should have] been published [two] times [by now].” So it’s a different standard…

[WriteWise]

You mention that in biology, especially, a lot of people talk about things as if they were fact because it’s already been published, and normally when you’re writing a paper, if it’s already considered fact within the area, you use present tense, right? So, in your writing do you use the past tense? Or do you use phrases like “such author et al. found”?

[Professor Chu]

“Such author et al. reported”…it’s a subtly in the language, but a very precise subtly…Try to use “report” rather than “found.”

Exemplary papers

[WriteWise]

Which of your own papers do you consider exemplary for its writing and science that you would like to suggest to students as reading material? Hopefully you could cite one in physics and another in biology.

[Professor Chu]

Laser Cooling of Atoms, Ions or Molecules by Coherent Scattering, Vladan Vuletić and Steven Chu, Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 3787 (2000).

Communicating terms to nonscientists

[WriteWise]

Besides being an academic, you also served as the United States Secretary of Energy. It’s rare to see a scientist in such an important governmental position. A challenge many scientists face is communicating science in simple terms to nonscientists, such as politicians. Do you have any tips for researchers and students in how to communicate the research to nonscientists?.

[Professor Chu]

Yes. First, it was unusual. I was the first scientist ever in the history of the United States to be a cabinet member. Not only in the Department of Energy, but in any department…

[While in this position,] I suggested that we put a price on carbon, a carbon tax, or at least begin the dialog…If you Google Steven Chu and Boston Globe there’s an op-ed piece explaining why there should be a carbon tax, why it’s better than cap-and-trade.. So [that op-ed piece is an example] that’s 900 words. How do you explain such a complex thing….?

[WriteWise]

In very simple terms….

[Professor Chu]

In simple terms to non-specialists. Now, it’s still a certain level. I try to…gauge what level of knowledge [the audience] has. In certain things, [the audience has] no level, so you have to build that level of knowledge, and you have to make good guesses. [When talking to non-specialists], you occasionally pause and say, “All right, does this make sense?” And when people just nod, it’s not good enough. And you try to engage a little bit in conversation and gauge what’s said. If [the audience] begins to ask questions on what was said, then you know they’re following. Right? If they’re just [nodding], then they’re probably thinking, “When is he going to leave?” So, when you’re in situations like that, you have to read the body language of the person. Ok?

[WriteWise]

Ok, very important.

[Professor Chu]

Very important. And I’ve also found, you should never overestimate the knowledge [of your audience]. It’s always better to underestimate. So you start explaining something and say, “Does this sound familiar?”

[WriteWise]

You ask them?

[Professor Chu]

Yes, and they say, most of the time, “Not really” and that’s good. If they say “Oh yes, I know about that,” then I go a little faster, go to the next level. But, it turns out that the really deep level of understanding [is when you can explain it on the] simplest level.

Author: WriteWise Team

The WriteWise Team is a dedicated group of specialists in academic writing, with vast experience in teaching and the publication process. The goal of our team is to impart valuable knowledge on a range of topics that will help students, researchers, and universities achieve their goals.

Posted In: Interviews,Nobel Prize

Tagged As: All Researchers,University Directors

Share Now!

Check out these other publications

Do you want to learn how to use ChatGPT for Academic Writing?

Show your love!

More Publications