Interview with Professor Melissa Moore

Category: Interviews,Other Experts -

Tags: All Researchers,University Directors

Table of Content

- Introduction

- Writing proposals comes first

- Get in the «good» pile

- Main advice: reading aloud

- Scientific writing advices

- Students writing advices

- Metrics and impact factor

- Mastering Bibliography for project

- Top Udemy ChatGPT Course – Take Your Academic Writing to a New Level!

- AI Writer for Academic Writing in Markdown Format

- Top 10 Best Productivity Hacks That Work

- WriteWise: National and International Recognition

- Recognition by HolonIQ: Top 200 Women in Edtech + LATAM EdTech 100

- 5 Easy Steps to Master the Format of the Bibliography for Project

- Among vs. Amongst

- The Art of Implication meaning

- Do you want to learn how to use ChatGPT for Academic Writing?

Reading Time 17.2 minutes

Introduction

Professor Melissa Moore, Principal Investigator of the Moore Laboratory supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Co-Director of the RNA Therapeutics Institute at the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

WriteWise had the honor and pleasure of interviewing Professor Melissa Moore, Principal Investigator of the Moore Laboratory supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Co-Director of the RNA Therapeutics Institute at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. Her research interests include eukaryotic RNA metabolism and the fate of defective transcripts.

Professor Moore has published over 100 articles in top-tier journals such as Science, Cell, Nature, Molecular Cell, The EMBO Journal, Trends in Biochemical Sciences, Genes & Development, RNA, Nature Structural Biology, Biochemistry, and the Journal of Biological Chemistry, among others.

In addition to this, Professor Moore is a dedicated mentor who believes in the future of “flipped classrooms” for teaching. Currently, Professor Moore has given two iBio Seminars that are completely open-access. Now you have the opportunity to be taught about RNA Splicing from a world leader on the subject!

Writing proposals comes first

[WriteWise]

How is the tutoring system at the University of Massachusetts?

[Professor Moore]

The University of Massachusetts Medical School is a separate institution from the University of Massachusetts. So, we only have students who are going to become MDs, PhDs or MD/PhDs. We don’t have any undergrads at all. Our graduate students must complete a writing course within the first year.

[WriteWise]

There is an official writing course?

[Professor Moore]

Yes! The ability to communicate science in a concise and compelling manner is absolutely essential for success in science. Getting money for your research and then publishing the results both require good writing skills. , In the second year of graduate school, we require our students to write a qualifying exam. This is a written document that discusses the background of their thesis project and what they plan to do. It’s like a grant proposal, so, it starts with specific aims, then a significance section explaining the background and outstanding questions, an experimental plan for how are they going to address the questions, and how are they will interpret the results. So the idea of the first-year writing course is to prepare them for this second-year qualifying exam. The qualifying exam is very much like any other kind of grant you might write. The idea is really to teach the students how to think about a project and then how to present it. These days, especially in the States, the academic funding has gotten much tighter than it was before. So if academic scientists are going to compete successfully for grants, they must be able to present their results and their ideas, in a compelling way. And if they can’t, then they’re simply not going to get funded. Of course, only about 20% of new PhDs ultimately stay in academics. Most go into something else like industry or government. But no matter your ultimate career goals, communication is the key. Whatever your job, you have to be able to present your ideas in a compelling way to advance your ideas and get resources. So it doesn’t matter what you’re doing, good expository writing a crucial skill for a PhD.

[WriteWise]

You mentioned that this course is more related with writing grants, but does it also touch on writing papers? Sometimes the format between the two are quite different….

[Professor Moore]

Writing papers, for us, comes more when the students actually obtain some results and start writing papers with their PI – that’s where they learn that. But grants come first because there are many graduate fellowships for which students can apply. Once a student gets a fellowship, it’s so much easier to get the next grant because now you have a track record of obtaining your own independent funding. This shows that you’re a go-getter and gives future grant reviewers confidence that you have the energy and passion to succeed. So the sooner you start that, the better. This is why learning to write proposals comes first, and then learning to write papers comes later. I also think it’s the right way to do it because it’s harder to write a paper without something to write about…

Get in the «good» pile

[WriteWise]

I have had the opportunity to read some NSF projects and projects from the European community, and I have discussed projects with many researchers. Basically, we all agree you have to put the core idea, the most important thing, in the first three pages otherwise –

[Professor Moore]

Actually, I think that the core idea has to be in the very first paragraph! Capturing the reviewer’s interest and imagination as quickly as possible is an absolute must. Let’s think about what a typical grant reviewer is facing: Many times for post-doctoral fellowships, each grant reviewer might have 10-20 proposals to read, and let’s say they’re six pages each. Almost no one relishes the opportunity to review grants – it is a task that must be done and is part of one’s community service obligation. So how does a reviewer get through that big pile? What I do is quickly go through the pile and divide it into proposals that I think will be fun or interesting to read versus those that look to be more difficult or not so exciting. Then I’ll start through the piles by reading and reviewing a «not so good» one, and then reward myself with a «good» one, and so on… So as a proposal writer, your goal is to get in my «good» pile, as I am already predisposed to like it.

[WriteWise]

How does one get in the «good» pile?

[Professor Moore]

It’s all about the first page (usually the specific aims page), and particularly the first paragraph. If the writer can convince me in the first three sentences of the first page why I should care about the work they’re proposing, chances are their proposal will go immediately into the «good» pile. Another factor is simply if I flip through the proposal, how «finished» it looks. If it’s poorly formatted with lots of typos, it’s almost invariably going to end up in the «not so good» pile. Finally, more words are not better – the best proposals are often the shortest, with generous spaces between paragraphs and reasonable page margins. Cramming in as much verbiage as possible by minimizing spacing just means more work and eye strain for the reviewer, and also sends the message that you aren’t able concisely communicate your message.

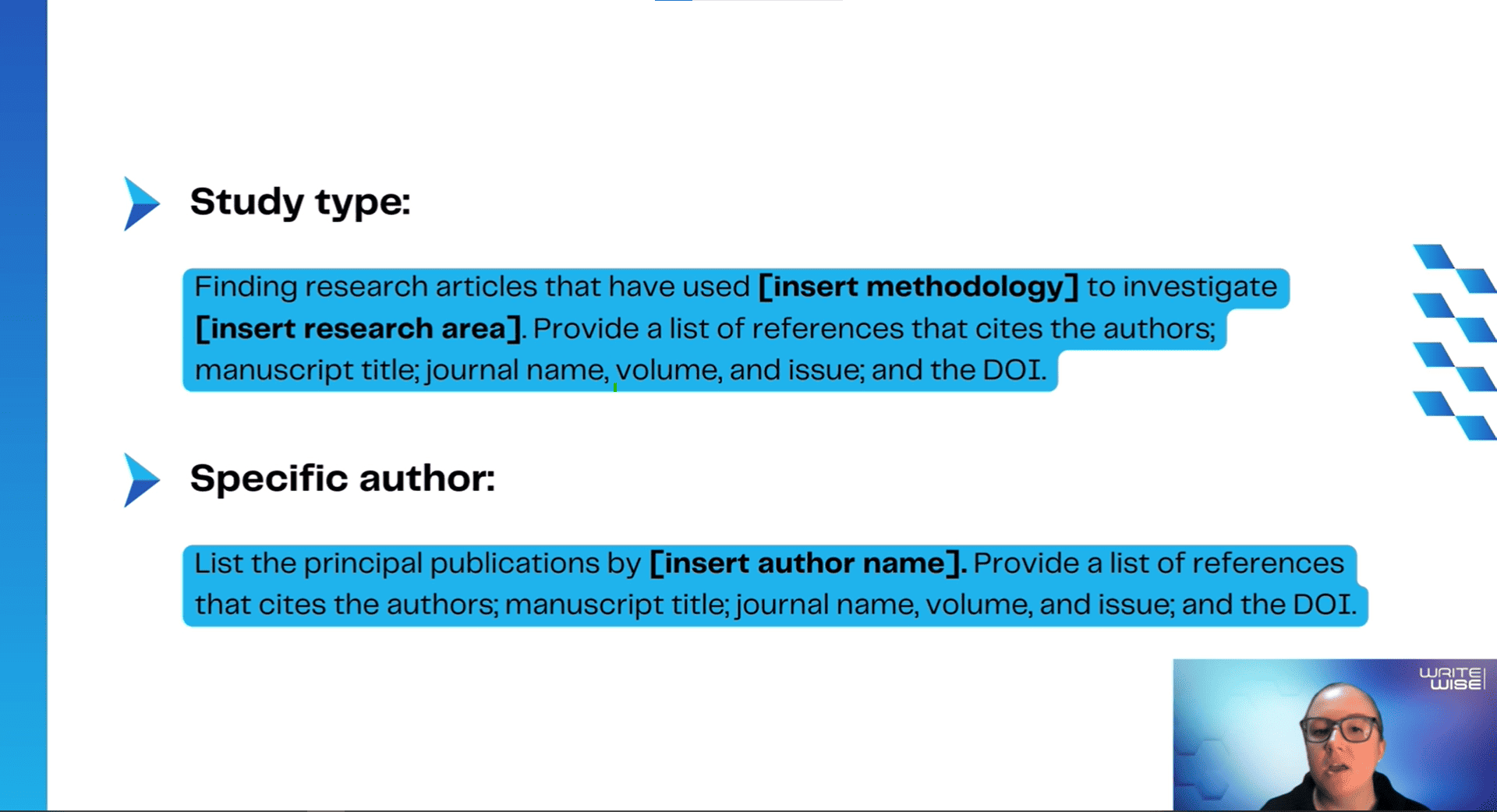

Main advice: reading aloud

[WriteWise]

In relation to projects and scientific manuscripts, does your opinion change if you know that the authors are foreign versus native English speakers? Do you give them a little more leeway about the language?

[Professor Moore]

If it’s a non-native English speaker and there are some small English problems, I’ll give them the benefit of the doubt, because certainly I couldn’t write in Spanish…

[WriteWise]

So, you look beyond the language and into the content?

[Professor Moore]

Yes, but it can’t be terrible. It’s been fascinating for me over the years to learn how different languages and cultural norms affect writing styles. One thing I recently learned is that in many school in India, students are graded by how much they write, not by the content. That’s crazy right?… Yes the important points might be in there somewhere, but the reader has to spend a tremendous amount of effort to find it. Romance languages like Spanish and French use many extra connector words, so those students tend to write incredibly long sentences in English liberally sprinkled with «of» and «and». On the other hand, Asian languages have no articles, so it’s hard for those students to learn where and when to use «the». So if English is your second language, an important final editing step is to have a native English speaker just go through and make sure it «sounds right». To make things sound right, one of my general rules for writing is, I’ll write stream-of-consciousness, but then I’ll go back and try to remove every two and three letter word that I can… Surprisingly, this makes it sound more like spoken English. When you’re reading something, it should have a voice ¬ it should really sound like someone is speaking. So, that’s why reading it aloud is so important when you are editing.

[WriteWise]

Wow, that’s the first time we’ve been suggested to read out loud. So, that helps you to write?

[Professor Moore]

Oh my goodness, yes. The other thing is, if you’re editing your own stuff, you’re often reading it really fast and missing stuff, but if you force yourself to read it out loud, then you can’t miss the mistakes. Also, if you have a hard time reading a sentence aloud, rewrite it. The best grant proposals and papers are perfectly understandable read aloud once, as though the writer is there in the room speaking directly to the reader.

Scientific writing advices

[WriteWise]

Another question, for students that are just starting to write papers and don’t have experience, one of the biggest challenges is just to start writing. What is your strategy to begin writing a paper?

[Professor Moore]

So, if it’s a standard paper with the Intro, Results, Discussion, Methods….do not start with the Intro! You start with the Results, and most of the time, before that, we try to make some figures. We mock up figures. We know they aren’t going to be the final figures…but it really helps you get an outline together…Once there is a general outline for the Results, and I ask the students to start drafting the that section, and, at the same time, they’re doing the Methods too because the Methods are much easier. So I say to them, you know, when I was a student, I really liked making figures, so I would use that as a reward for myself. I would make myself write a section, and then I would let myself make a figure. But whatever you like to do, use that as a reward for yourself. I was just talking to one of my students who was having a hard time writing his dissertation and he didn’t yet know this [system of rewarding yourself]. He said, “You know, I’m spending all this time sitting here, and I’m not running.” And I said, “But you like to run! Make running your reward.” This completely got his writer’s block to go away and he increased his health to boot!

The biggest mistake is starting with the Introduction, which is the last thing you should write. Start with the results, and then, as you’re writing, think about the Introduction. What do I have to tell my reader so that they will understand my paper? As you’re writing the Results, jot down points to put in your Intro so that you remember them, but don’t attempt to write the Introduction until last…

Also, I try to start writing the paper when I think we have somewhere between 50-80% of the data. Sometimes it takes us quite a long time to write a paper because we’ll start and write for a while, and then [the students] will have to go back and do another couple of months of experiments, and then we’ll come back to writing. It cannot be the expectation that “okay, now we’re done, and now we’re going to write.”

[WriteWise]

And how long do you take to write a paper?

[Professor Moore]

Well, it can take up to a year…it tends to be a much better paper if you start writing when you’re a little more than halfway there with the data, because it helps to tell if you’re going in the right direction, instead of saying “here’s the data I have” and trying to make your story fit that. So, the earlier you can start writing, the better.

Students writing advices

[WriteWise]

So, a lot of times, students can become a little lazy. I wondered if you put a deadline on their writing process, but it appears not….

[Professor Moore]

You’re going to laugh now, about my writing sessions. I’m not very good either about getting things done on a schedule. The only way I can get things done is if someone is sitting in front of me making me do something. I also don’t like the thing where I get a written document from somebody and make some comments and hand it back. I’ve found that to be very inefficient. So, the way it works in my lab, and a lot of other people have started using this approach when I’ve told them about it, is that I have the first author(s) write some sort of draft. It might just be the first couple paragraphs of the Results, and then we make a time…usually a 2-4 hour block…[and] I’ll sit with the author(s) and we just write in real time on the computer. So, they get to see how I write, and then they learn so much better. Pretty soon, I’ll get to a point where I’ll say, “What do you mean here?” and they’ll explain it to me out loud. Then I’ll write something down that captures what they want to say in a better way…so, for each student, I can tailor what they need to work on in their writing style.

[WriteWise]

Wow, that’s just great. I think the learning process for the student must be wonderful.

[Professor Moore]

Yes, and it’s rewarding for me too! Not only do I get to spend lots of quality time with each student, but after I’ve worked with them for a while, their writing will improve to the point where eventually I hardly need to edit it at all. That makes me so happy and proud of them. It just gives me such a good feeling; they really show progress.

[WriteWise]

It’s a good investment for you too. You give the time to teach, but then they know how to do it.

[Professor Moore]

Yes, as each student learns better writing habits, the whole process speeds up, the students feel good about themselves and the investment pays off.

Metrics and impact factor

[WriteWise]

You have published several times in Cell. Besides exceptional contribution, quality, and novelty of the research itself, do you have any practical advice in terms of scientific writing for this journal as compared to other journals?

[Professor Moore]

Well, to publish in Cell, you have to have a big story supported by many different kinds of data. So it’s typically a long paper years in the making. By big story, I mean it has to be something that changes the way people think… And the highest compliments I can give a paper are two words: elegant and disinterested. Elegant has to do with how the experiments were designed and executed, and how beautiful the data are. Disinterested doesn’t mean «not interesting» – it means the writer was not trying to push a particular point of view…That’s something I see in a lot of research papers that I don’t like. It’s the idea that you have to sell your stuff and try to make people believe something. Our goal as scientists should be to discover something important, then write a paper about it and have that paper still be true 50 years from now. I never want to publish a paper and then two years later have it proved incorrect. So, if you’re disinterested, you’re considering all the possibilities. You say, we did this control and this control, and we ruled out all of these other things. So that’s what you need for a Cell paper.

[WriteWise]

There is a lot of pressure on researchers to try to publish more to try to increase the metrics. I’m sure you know that good and cutting edge science takes time. What is your opinion about this situation?

[Professor Moore]

If you look to the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and what their standard is, that’s the standard that should be used. Basically what Hughes does, which is different from most funding agencies at least in the States, is to invest in the researcher. So they pick promising researchers and say to them we’re going to give you five years of really generous funding to do whatever you like. At the end of five years, come back and tell us what you did with it. If you do something great, then we’ll give you another five years. So they’re not telling you in advance what you should do. But in order to get renewed at Hughes there’s something called the deletion principal. And the deletion principal is as follows: If you take what you did in the last five years and just completely delete it, imagine those papers didn’t exist, if it doesn’t make a difference to the field, then you’re not doing what we expect of a Hughes Investigator. So you have to be doing science that makes a difference. The number of papers is not important. Your contribution can be just one paper that completely changes how people think. Thus they care about impact. But impact is not measured by the impact factor of the journal, it’s the long-term impact of each individual paper. So that’s what scientists (and their administrators) really need to consider. But how do you quantify the impact of an individual paper? One way is to count citations by other authors. If a paper has been out for a while and it is important, it will have received numerous citations from other researchers in the field. On the other hand, some researchers publish a huge number of papers, but each paper gets just a few citations, and mostly these are the same researcher citing his/herself. How much difference can this be making for the field?

The key [to good science] is to give young people freedom…Because when you’re young you have the energy and motivation, and that’s when [scientists] can do their best work. Then when they get to my age, they can still be doing good work, but also focus on training the next generation…..

Science is an apprenticeship…[We] need to get away from this idea that teaching equals lecturing. Harvard Medical School has just flipped its curriculum. They’re not going to do lectures any more at all, and many schools are going to this. Now with video, why should I stand up in front of a class and give a lecture? I just videotape my lectures and then students can view them at their leisure. Or better yet, view a iBiology lecture anytime by the best lecturer in the world on their topic… That’s so much better than having to sit in a too hot or too cold room listening to somebody who isn’t really an expert and maybe isn’t even all that good at lecturing… So for my students, viewing lectures is now their homework. It’s better to spend [class time] with students reading a paper and discussing, or solving problems in small groups. So, I predict that over the next couple of years the whole real-time lecturing thing in front of a room full of students will go away…

[WriteWise]

It’s a bit like the Khan Academy, where the lecture is the homework and the classroom time is spent solving the problem and moving all students forward.

[Professor Moore]

And with graduate students, you’re working on solving the problems that their own data have generated, so you’re working with new stuff never seen before.

[WriteWise]

Which is definitely more interesting.

Author: WriteWise Team

The WriteWise Team is a dedicated group of specialists in academic writing, with vast experience in teaching and the publication process. The goal of our team is to impart valuable knowledge on a range of topics that will help students, researchers, and universities achieve their goals.

Posted In: Interviews,Other Experts

Tagged As: All Researchers,University Directors

Share Now!

Check out these other publications

Do you want to learn how to use ChatGPT for Academic Writing?

Show your love!

More Publications